From Series A to Exit: Mastering Metrics

7/9: Finance - Growth

9 Min Read – What You’ll Take Away

Too many CEOs have limited knowledge about Finance. Be as curious about Finance as you are about the product or your Sales pipeline.

VC math demands us to start with a multi-billion dollar market. And expand into a 15B+ industry.

Don't confuse means with the end: Raising capital is fuel for the ship; not the landing spot.

There is no one-size-fits all strategy to raising: Context matters if we don’t want to be choked out 24 months down the road.

The best budgeting trick? Stop rewriting it every month: Plan once, then move closer every quarter.

Underpromise, overdeliver: The virtue of building great relationships with investors, banks, and shareholders.

Separate investor expectations from team motivation: Run an external plan to secure funding and an internal one that pushes the team to excel.

Finance is the adult in the room: Not every initiative gets funded; and it shouldn’t. A great CFO guides us on when to go all-in and when to hold back.

Every initiative needs to come with clear short-term wins: Proof points that we’re creating value and small successes to rally the team.

Accountability dies without committed goals: We can’t hold teams responsible if expectations were never clear in the first place.

From Series A to Exit: Mastering Metrics

Despite what you may think, the recipe for reaching your next financial milestone doesn’t have to be a black box. In “From Series A to Exit: Mastering Metrics”, we break down what it takes to position your business as an attractive investment - be it for funding or a strategic exit. Each article focuses on a core function critical to your success:

Finance - Growth,

and People.

In addition to my own experience, my co-authors draw on their success stories from the likes of Uber, Booking, Dropbox, LinkedIn, Just Eat Takeaway, Lightspeed, Miro, EasyPark, Bynder, Squarespace, BlackRock, JP Morgan, Ares, and more

Mastering Finance Metrics

Joining me for today’s dive into Finance are CJ Gustafson and Jos van Schaik.

Having CJ featured in my humble newsletter? Total fanboy moment. Throughout his career, he’s advised on M&A at PwC, worked in private equity at Providence Equity Partners, and held multiple CFO and FP&A leadership roles in high-growth tech. But most impressively, CJ has built a massive following through his must-read newsletter Mostly Metrics (with over 60,000 subscribers) and his podcast Run The Numbers, which has given me unparalleled insight into how the best CFOs run their shop.

From Calendly, Ramp, and Olo to PayPal, Plaid, and GoDaddy: CJ has had some of the sharpest finance leaders in tech on his pod. Featuring his take in my own newsletter is a bit like bringing a young Maradona to my Sunday league football game.

With 20+ years of experience in tech, Jos has witnessed the shift from licensed Software to SaaS first-hand. Having led Finance at Speakap, Dealroom.co, Omnia Retail, and Bird and having supported dozens more as a fractional CFO, Jos knows exactly how to get investment-ready. Understanding the metrics that matter and how to move them makes Jos the perfect puzzle piece to bridge Finance and Strategy and a rare breed of CFOs with an operator mindset.

When other teams build the product or bring in customers, it's easy to think of Finance as a back-office function: a numb, reactive reporting center that complains about us spending too much. But in reality, Finance fuels the entire machine: they get us the capital to exploit the opportunity, then control the throttle and keep everyone honest on their progress.

Too many CEOs hire glorified accountants to “handle the numbers”: it’s a blind spot I’ve seen cost us dearly. In today’s edition, we’ll explore how the best CFOs don’t just close the books but help drive enterprise value. And how you can tell the steak from the sizzle. Great CFOs need to help shape the story investors buy into, hold the line on what the business can afford, and partner cross-functionally to improve its underlying mechanics: margins, payback, retention, and more.

Over two articles, we’ll show how great Finance leaders guide, control, and enable the business - specifically through the lens of fundraising and exits:

Analysis + Capital + Execution: How Finance Enables Growth,

Numbers, DD, and Deal Management: How To Run An Exit.

Part 1: How Finance Enables Growth

Any externally funded venture has the same objective: Exit. When I think of Finance and its role in getting us there, it’s equally about leading the process of a raise or sale as it’s about supporting the growth and professionalization of the business in the first place. Great CFOs and their teams, therefore, don’t just record what happened but shape what happens next.

“Controlling and FP&A are two different muscles. One tells you what happened. The other helps you plan what’s next. Great CFOs build both disciplines.”

Jos van Schaik

It’s this diversity in responsibilities that drove the trend from simply hiring Accountants and ex-Consultants towards the “modern CFO”: someone who has experienced multiple aspects of the business, can level with its leaders, and help move the levers necessary. You need to have run every part of an org if you want to lead and improve it. CFOs often miss this. And the pulse of the business.

Analysis + Capital + Execution. From sizing our ambition and funding the plan, to protecting margins and owning the story behind the numbers: let’s break down what best-in-class CFOs and their teams actually do to grow enterprise value.

1. Modeling

All starts with sizing the opportunity and modeling our ability to capture it: How big is the prize? What will it take to capitalize? Ever wonder why every pitch promises a EUR 10B market? Because VC math means we have to.

The Raise: VCs typically aim to own 15–25%. Since their winners need to pay for all the losses of the fund, they need us to 5–10x in value to make their return. So a VC investing EUR 50M at 20% is hoping for an exit between EUR 1.5B and EUR 2.5B.

The Valuation: Following the math of the raise, we'll need a EUR 200–250M post-money valuation. Assuming the short-ish-term target being a reasonable 10x ARR multiple, that means we'll need to quickly grow into EUR 20–25M in ARR (with strong margins, retention, and big remaining TAM).

The Market: A EUR 2B exit valuation at an 8-12x ARR multiple means we're expected to show EUR 200-250M in ARR. Most back-of-the-napkin VC math caps us at 5–10% market share. Targeting EUR 250M ARR, that means we need to prove we’re in a EUR 2.5B+ market - today!

Wonder who'd buy a company nibbling on a EUR 2.5B market for EUR 2B? Exactly! That's why we need to grow our TAM over the years: find new opportunities vertically and horizontally to show buyers the additional upside. Likely of a EUR 15B+ industry.The Performance: It's not only about capturing the opportunity but doing so at a reasonable cost. If CAC is too high or margins too low, the multiple goes down and the math quickly breaks. That’s why high-volume, low-margin models (e.g. payments) raise red flags to me: the unit economics only make sense at massive scale. Reaching that scale requires deep-pocketed, conviction-driven backers. Most - especially in Europe - don’t have enough of either.

“All good modeling comes down to asking: What has to be true for this to work?”

CJ Gustafson

To make sure we successfully walk that thin line from the get-go, a great CFO anchors our budget to the size of the prize, the cost to capture it, and the expectations of the next round. They help us reverse-engineer the raise we can justify, the milestones we must hit, and the runway we need to get there.

2. Budgeting

Whatever the strategy to capture our opportunity, Finance helps translate that strategy into numbers: What are we expected to earn by EOM, EOQ, EOY? What does it cost? Can we afford to hire that talent, enter a new market, launch a second product line, or fly our team to Ibiza?

That also means splitting spend across horizons: KTLO (Keeping The Lights On) to maintain the core, 1–2 year bets to accelerate growth, and longer-term plays that expand TAM or solidify moat.Smart budgeting is how strategy gets funded. But I’ve rarely ever seen a vertical owner (e.g. Head of Marketing or Sales) give the CFO a budget to hit their milestones (zero-based budgeting). Instead, they ask: how much do I have? The best CFOs I’ve worked with can balance both: they have the experience to offer a starting point, then enable and coach the teams to gather data and figure out the cost of their plan for the next cycle. It’s also where a seasoned operator comes in handy - whether in the shape of a COO, COS, or as an advisor.

Whenever we set a budget, it’s based on assumptions: how much can we capture, what does it take, how much does it cost?

“Most companies have poor forecasting not because they lack data but because they haven’t made the underlying assumptions explicit. Once you do, it becomes easier to test, learn, and update. Rather than starting from scratch every quarter.”

Jos van Schaik

Things get interesting once we miss the original budget. While constantly updating our forecasting is crucial to know where we’re heading, it’s equally important to understand why. A great CFO doesn’t just spin up a new budget every quarter when we miss the old one but helps bring us closer to the original plan over time.

“The best CFOs compare forecast vs. actuals to ask: why did we miss? Was it execution? Assumptions? External factors? You’re trying to close the loop - not just update numbers.”

CJ Gustafson

When it comes to budgets, forecasting, and actuals, we need to treat them as a dynamic muscle, not a static spreadsheet. If the original plan was wrong, we can’t just abandon it or update expectations. We need to close the gap, course correct, and build forecasting precision over time. In other words:

Improve execution (Operational Excellence; COO) through experimentation and figuring out what worked and what didn’t;

Improve forecasting by feeding real historic data back into the model (CFO).

A strong CFO helps us understand why we missed the plan and whether that miss was executional (e.g. delayed hiring, missed campaigns) or strategic (wrong bet). Over time, this feedback loop makes the budget more realistic, the team more accountable, and forecasting more useful in decision-making.

What happens when you don’t have that loop I could see at Convious. We had missed OB (original budget) but instead of challenging the underlying assumptions, we just kept rolling the pipeline one quarter forward. Everyone knew New Business was behind. But no one could say: “We were too optimistic. We just can’t hit this.”

“Forecasts aren’t meant to be correct. They’re meant to be directionally correct and get everyone aligned on where things are heading. But once you show that forecast to investors, it becomes a commitment.”

CJ Gustafson

All because the budget wasn’t just a forecast but a promise. Our last raise had been based on a COVID-fueled sales peak. When that growth proved to be temporary, headcount was scaled down accordingly. But the targets remained. We were expected to double the business without clear PMF, definitely without GTMF, and without the team to make it happen. In an ideal world, you scratch the old plan and rebuild from what’s real today. But with capital raised on a different story, we were boxed in. A new budget would’ve admitted the dire truth: the plan no longer worked. So instead, the forecasts stayed pretty and the gaps got bigger every month.

“The golden rule? Underpromise, overperform. That track record becomes incredibly valuable in conversations with investors, banks, or shareholders.”

Jos van Schaik

Another way to shield us from investor pressure - and a best practice from my time at Convious - is to run two budgets in parallel (internal; external). One that pushes teams internally to (over)achieve and one that underpromises results to investors - giving us room in case we’re behind for a month or two. My usual rule of thumb to balance both:

build the internal one realistic enough for staff to be motivated

and the external one just ambitious enough to sell the dream to investors.

3. Capital Strategy

Scott Galloway once put it perfectly: No startup makes sense at its inception. Until it does or doesn‘t. Entrepreneurs are storytellers. It’s their job to deploy a fiction that captures the imagination of others and attracts capital to pull the future forward and turn rhyme into reason. The only way to predict the future is to make it. Great entrepreneurs believe their story will come true.

When it comes to fundraising then, many confuse a mere financial tool with any relevant outcome - I constantly see founders celebrate successfully attracting capital: whether it’s the amount raised or their latest valuation. Sure, it’s a confirmation: a recognition of the work you’ve done so far. But let’s not mistake a raise for anything more than what it is: a means to an end. Memento Mori - the real work hasn’t even started.

“It’s fuel for the ship. It’s not the landing spot. Put the money in the bank and keep building. I’ve seen lots of companies lose operational momentum because all their efforts go into raising funds.”

CJ Gustafson

The better our CFO runs this process, the less disruption we’ll feel on the business. From timing our raise, over deciding between equity or debt, to structuring rounds that fuel growth without crushing dilution: Finance needs to own the capital strategy and a great CFO considers all internal and external factors strategically when running this process from end to end.

A. Timing

Ask five people about how to spread out your rounds: you'll get five different answers. There are so many schools of thought: raise only as much as you need, raise when you don't need the money, raise as few rounds as possible, raise whenever and however much you can when the conditions are great, ...

“Taking capital through each round has a cost in the form of dilution. If we can minimize the amount of rounds, we’ll keep more for ourselves.”

CJ Gustafson

Immad Akhund, founder of fintech Mercury and previously Partner at Y Combinator swears on raising capital infrequently and only when he doesn't need it. Mercury has only done four rounds in eight years (2017, 2019, 2021, and 2025). According to Immad, this has three major benefits:

Less dilution: Every fundraise costs equity. Fewer rounds mean less dilution over time.

More time to build: Fundraising is a full-time job that takes founders away from building. When we raise less frequently, we have more time to spend on what really drives value.

Progress between rounds: With more time between rounds, we’re able to show substantial progress that justifies bigger jumps in valuation.

This approach differs significantly from traditional VC wisdom. They mostly want to fund 18 months of burn with a specific plan. For Immad, however, optimizes for maximum valuation, raises a substantial amount, and manages it carefully. When they raised USD 120M in 2021, he admittedly had no idea how they'd spend it. But he felt the market was hot, their metrics were strong, and it made strategic sense.

All of it requires strong unit economics and investor interest - it’s a privileged situation to be in. But for those who can manage it, raising from a position of strength rather than necessity not only shifts our weight from the back to the front of our feet when negotiating - it gives us and our teams peace of mind and a higher appetite for risk when building.

“If there’s a fair market deal when you’re raising - take it. Optimize for the raise and maximize for the exit - since there’s just one.”

CJ Gustafson

Timing isn’t just about our cadence, however. It’s just as much about readiness for external capital. Many early-stage founders can’t wait to give in to external interest and raise first funds - eager to build and proud of a valuation that makes them multi millionaires on paper. But it can cost more than many probably think.

Most VCs aim to take 15–25% ownership per round (pre-dilution). Means: raising EUR 5m often requires a EUR 20–25M pre-money valuation. If we’re still early and doing, say, EUR 1.5M in ARR, that implies a 13–17x revenue multiple. That’s a level even top-tier SaaS companies rarely sustain at scale.From that moment on, we’re racing to grow into our own valuation. That pressure compounds across rounds and limits our room to maneuver. Unless we truly need external capital to unlock our next stage of growth, we should consider waiting. Dilution is permanent.

B. Ticket Size

We can all agree: the best time to raise isn’t when we need the money. It’s when the market is hot. But if we raise too much without a clear plan to allocate the funds, we risk losing discipline. Capital starts flowing into areas it shouldn’t. Focus blurs. Efficiency drops.

“We have to deliver return on investment. Oversubscription cultivates the risk of overspending.”

Jos van Schaik

While it worked for Mercury and many others, Immad’s philosophy comes with a major caveat. To my surprise, many founders forget three simple truths:

A valuation is a promise into the future. It comes with clear expectations and the more mature the business, the more our valuation is based on historic data. If we can’t catch up in time, the next raise is going to be a lot harder.

Investors expect us to put money to work. Their funds have clear life-cycles. That’s why most of them expect us to work on 18 months timelines.

Investors eventually expect to get their money back. Every EUR or USD we burn through, will have to be earned back later on.

“It also depends on the round: real greenfield with lots of potential but still a lot to develop? We'll find ways to spend the money. But in a Scaleup, I'm less comfortable taking on more capital without a specific scenario. Best practice is to have two or three scenarios with different strategies, growth projections, and burn.”

Jos van Schaik

One way to balance macro opportunity with internal readiness is to park the cash temporarily and earn 4–5% interest. But even that privilege comes with equity-level dilution. Unless the money buys us clear, short-term strategic flexibility (e.g. optionality on M&A, hiring key talent, or a buffer in volatile markets), investors will expect us to put it to work - fast. If done right, we avoid valuation greed and oversubscription (without a clear reason). One often leads to down rounds and painful preference stacks, the other one to bloated teams and burn.

“All that matters is that you’ve got enough capital to reach meaningful milestones. I’ve seen founders raise just enough to avoid a high valuation bar but not enough to actually prove the business. It just kicks the can down the road.”

CJ Gustafson

C. Valuation

This just goes to show how smart we need to be about early-stage fundraising. I’m generally all for the pathos of “crossing the bridge when we get there” but when it comes to raising capital, we have to think a few bridges ahead. Raise at the right price, from the right partners, with a clear path to grow into it! Anything else has us buy time today but starve us later: we’ll be stuck in the dead zone - too expensive for new investors, too early for buyers, and with a cap table no one wants to touch with a ten foot pole.

💡 Reality Check: Benchmark what you're actually worth!

For founders trying to reverse-engineer their next round, this valuation calculator by SaaStr and Carta is a great directional tool. It uses anonymized US startup data to estimate valuation ranges by stage, sector, and ARR. It also considers the love investors still have for AI.Note: it’s based on US data. Driven by smaller exit expectations, lower investor competition, and more conservative growth assumptions, European valuations are typically 20–40% lower at the same stage and revenue level.

And don’t count on investors to tell you what’s right: their incentives aren’t always aligned with ours. Even if the point-guard on your deal might not be around for the next raise, they still got their allocation bonus.

D. Vehicle

But if we really need additional money to capitalize on opportunities, there is another way to fund growth: debt can be a powerful tool but it comes with its own challenges. If revenue is predictable and margins are healthy, debt helps us fuel growth without giving up another 20% of the company. It’s also fast: no pitch decks, no roadshows, no cap table drama. While raising equity can take 6+ months, a loan can hit our account within weeks.

“The type of capital we take dictates the decisions we make. Raising equity, venture debt, or doing a SAFE: they all come with different timelines and expectations. Don’t sign up for a growth story if what you actually need is time to build.”

CJ Gustafson

I often hear the argument of tax deductible interest but for pre-profit startups, that benefit merely comes in the shape of a tax credit you’ll never use. As a startup CFO, I don’t care about credits 7 years down the road - I care about cashflow and survival during the next 12-18 months.Since PE firms build their entire thesis on leverage, it’s no surprise they love to see a balanced debt-to-equity ratio. To them, smart use of debt signals discipline and understanding of capital-efficient returns. But banks don’t lend to businesses that are about to go belly up. So if we want debt, we need to earn it by showing we’re in good shape to repay.

The ones who aren’t in that shape often turn elsewhere: to loan sharks offering venture debt. This is an entirely different beast. It often comes with tight covenants: miss your growth, margin, or profitability targets and they can call in repayment. First hand, I’ve seen this bring a business to near collapse - overnight. And it’s not just the principal! Prepayment penalties, high interest rates, and warrants that take a bite out of the upside can quickly turn what initially felt like another lease on life into your worst nightmare. Some lenders even stack on covenants around cash interest coverage. Meaning: it’s not enough to grow fast; we have to prove we can fund interest payments from recurring cash.

I’ve seen things quickly turn from bad to worse when that sort of debt sat on our books during exit talks. Strategic buyers are used to working around debt. But when those obligations can’t be restructured (i.e. they have to be repaid immediately in case of an exit), they’ll make sure to have us pay for it. Meaning in practice: a bigger chunk of our own payout gets pushed into the earn-out. We carry the risk of execution post-sale to earn our keep while the lender makes a killing on the close.

That’s usually when CEOs get curious about what their CFO cooked up over the past 5 years. But at this point, it’s too late. So what does all of this come down to? The importance of a CEO to be as interested in Finance as they are into the product or their Sales pipeline. So they hire and challenge a CFO to combine all this context into a smart capital strategy we can rely on from day 1: one that funds our exploitation now and doesn’t choke us out 24 months down the road.

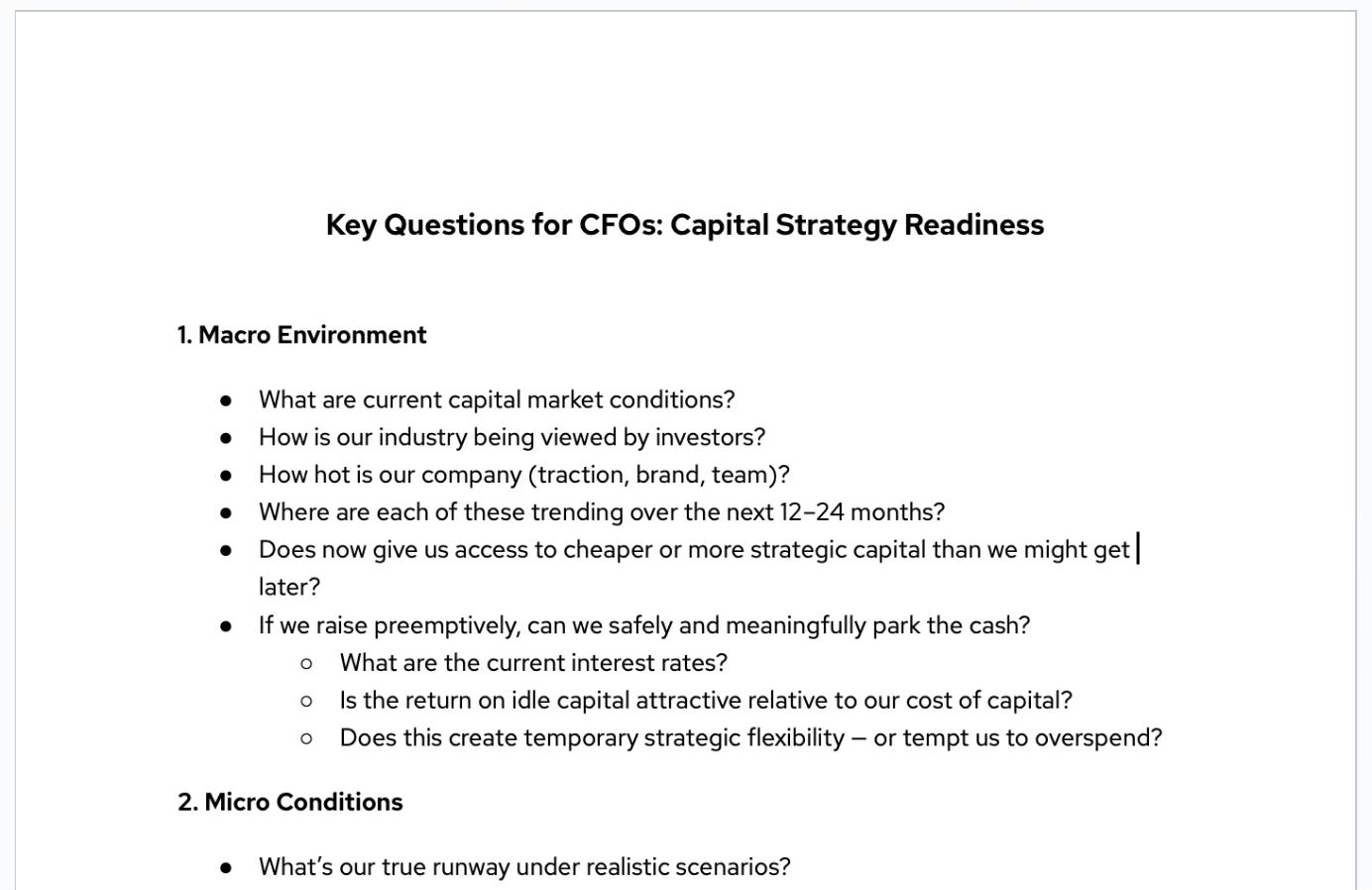

If you want to up your chance of hiring someone who can deliver fuel at the best terms: ask them some of the questions below. If you’re a CFO, use it as a mental exercise to make sure you’ve considered what matters.

4. Allocation & Prioritization

Not every initiative gets funded. And it shouldn’t. Finance protects our margins by challenging teams on tradeoffs:

Are we investing in initiatives with measurable return?

Are we spending to penetrate, to scale, or just to keep the lights on?

My first exposure to Private Equity was also the first time I heard about the Rule of 40: the balance between growth and burn. What initially felt like someone just closing the tap turned out to be about something else entirely: discipline, prioritization, and context. Of course we want to do it all: grow new business, expand existing clients, enter into new markets, acquire a competitor, move upmarket, and layer in new revenue streams. But life is about compromise. And when we deal with someone else’s money, we have a fiduciary duty to balance their risk profile with our joint objectives.

“I think it's worth distinguishing budget from plan. A plan is ‘here's what we'd like to do and what we think it'll cost.’ A budget is ‘here's what we're going to do because you gave us this much money.’ The former allows for exploration, the latter creates accountability.”

CJ Gustafson

Being disciplined and diligent means we don’t blindly bank our entire runway on new strategic directions. New bets are initially budgeted for experimentation: land, then expand. Figure out what works, then double down and replicate. Every initiative needs to come with clear short-term wins: proof points that we’re creating value and small successes to rally the team.

“In my world, I look at line items on the budget as little experiments. They don’t all have to work, but they need to have some type of checkpoint or short term marker that indicates progress or promise.”

CJ Gustafson

A story from one of my last assignments serves as an example of what happens without that discipline or without the time and capital to afford diligence. We were in the middle of building out self-service kiosks - a strategy already based on minimal proof points: mostly hearsay, vague assumptions, and badly collected RFLs. Making the necessary changes required a massive product, operational, and financial effort that sidelined many other - often KTLO - initiatives. With the AI hype in its baby shoes, it was announced we’d start pushing an AI chatbot instead. Sure sounded exciting but it was yet another initiative for a team already behind and strapped for resources.

“Finance should operate like the adult in the room. A great CFO guides us on when to go all-in and when to hold back.”

CJ Gustafson

We should’ve paused to find answers to the most rudimentary questions:

What is the world we want to live in (10 year vision) and what is our place in that world (5 year mission)?

Who are our customers then and today, what do they want to achieve, what is and likely will be holding them back?

How do we plan to help them bridge that gap now and in the future?

Those are questions most CEOs don’t want to hear when they’re with their back against the wall. But those are the ones that need to be answered before making any sort of strategic bet. And they are the kind of answers a CFO needs in order to sell our timeline to investors. In the end, it’s not like failure came down to a CFO who couldn’t say “no”. As so often, it was the lack of diligence that messed us up: we didn’t have a grounded and clearly aligned strategy across C-level leadership, management team, and the board. Instead, we were just reactively jumping on the next shiny object expected to buy us another 12 months of runway.

“I see people get so obsessed with adding logos or opening new revenue streams that they forget to validate what already works. The best companies I’ve worked with are the ones that say, ‘we know exactly why customers choose us and we optimize that into a machine.’”

CJ Gustafson

In contrast, my time at Formitable & Zenchef, then, serves as a best practice: together with PE firm PSG, I clearly defined where we wanted to be in 3, 5, or even 7 years. It’s not about being able to predict the future (who knows what the world looks like in 5 years) but about understanding which foot comes in front of the other. We need to set milestones together with our investors, then work backwards to understand what we need to prove, build, or scale to hit that goal. That’s how we know which initiatives matter now and which ideas are distractions. The collaboration with our CFO was a natural symbiosis: I provided the qualitative vision, direction, and some mile markers; he translated it into revenue, cost, and a budget.

Side note: Reflecting on the two examples above, mismanagement only further manifested mistakes already made much earlier — rooted in a flawed capital strategy.

Pressure from past raises made it near-impossible to pause and question what we’d previously sold as truth. The only real solution I saw was a financial reset wiping everyone out. But that fear naturally cultivates a strategy based on hope and tends to push us to hunker down rather than course-correct.

At Formitable, on the other hand, we had deep-pocketed investors with a long-term view. Even though we didn't need to at the time, we could've afforded to pause and reassess.And that’s the point: financial discipline isn’t about austerity - profitability obviously isn’t and shouldn’t be the only goal regardless. If our market is huge and penetration still low, we need to invest in growth. What PE taught me was this: the question isn’t just “is the business profitable?” but “which parts are?”

“Fine to be growing and unprofitable. But the CFO needs to know exactly where the profit is made or lost.”

Jos van Schaik

We don’t need every bet to pay off right away. But we do need to know where we’re burning money and where we’re making it back.

"We saw certain Google Ads campaigns driving higher-value buyers - but they were more expensive than our blended CAC goal. Instead of obsessively optimizing for the lowest CAC, we doubled spending on those high-LTV segments - and revenue followed."

Sebastiaan Smits

5. Creating Accountability

Speaking of burn: Every EUR on the budget’s spend connects to an expected result. As COS or COO, I make sure we hit our targets. But it’s the CFO who ultimately owns the scoreboard. They report the actuals, track costs against budget, and highlight when we're ahead or behind plan. Whether it’s revenue, burn, or margin: they surface the numbers that keep everyone grounded. And they maintain the single source of truth.

Getting teams to contribute and driving accountability across the team, however, only works if we all have clearly committed goals to be held against. Bottom-up contributions only make sense if they are part of a clear storyline that’s connected throughout all meta-levels:

Company Objectives = top-down strategic intent.

Where are we trying to go and why? What’s the achievement?Budget = translation of expectations into numbers.

What lagging metrics do we need to hit to be on track? What’s it going to cost?Team Goals = bottom-up contributions and ownership.

How does each team contribute to our objectives? Where do we focus to hit the budget? What do leading metrics tell us about progress? Where do we need to make changes?

The CEO and their leadership team determine the high-level objectives.

The CFO builds the budget and maintains the scoreboard.

The COO or COS helps teams shape their path to get there.

All of them eventually hold the teams accountable.

“If you’re missing your numbers, stop talking about your ARR or your churn. Start talking about leading indicators that prove you’re heading in the right direction: win rates, pipeline coverage, or product usage. Investors want to know if the car is still on the road.”

CJ Gustafson

We’ll dive deeper into OKRs - and my hard-earned lessons from implementing them across different companies - in the People article of this series. That said, they’re not just an HR topic. Goal-setting plays a crucial role in Finance, too. The OKR framework and the book "Measure What Matters" was never meant to be a plug-and-play blueprint. It's supposed to be intellectual stimulation. Food for thought. We all have to figure out our own best practice on how to steer and empower our teams. Whatever the method, we'll likely have to go through an 18 month cycle to get it right. If ever.

In my experience, planning takes as much time as we give it. The more time we spend, the more we risk over-engineering it. But the moment we understand which levers drive value, planning becomes far simpler: it’s all about the business flywheel. Getting those levers right, is core for any business at scale. We finally have historic data to shape and validate our assumptions around what drives value. If we master all our core pillars, the business will be doing great. If we quantify them, their improvement can serve as our objectives.

In turn, if anything is not working as expected, we can go back to those levers and drill down to see what needs fixing. It's an ever-recurring theme in business: land, then expand. Understand, then replicate.

Without the ability to understand what's going wrong and why we're off, we'll just end up building another budget and adjusting our forecast every quarter.“A budget isn’t something to rewrite every month. If you have to, it wasn’t a good one to begin with. The goal isn’t to get it perfect but to get closer. To understand why we’re off.”

Jos van Schaik

Convious serves once more as an example for what happens when we don't get those right. When we skip the hard work of discovery and rush to conclusions. When we're so blinded by sudden success, we believe we struck gold but have no idea why. If the results are great, we get unrealistically ambitious. If things go wrong, we mistake symptoms for root causes. Without knowing the levers that drive success, we wont be able to move them.

Up next...

Numbers, DD, and Deal Management: How To Run An Exit.

In Part Two, we’ll cover what different buyers care about, how to prep your team for diligence and break-out sessions, structuring your story, and building relationships that make for a fast, clean close. We’ll share all the best practices on prepping your data room, nailing your QofE, and avoiding common pitfalls around SARs and misunderstandings on equity vs enterprise value.

With years of experience advising entrepreneurs and leading businesses through multiple successful exits, I bring a unique toolkit of frameworks, strategies, and best practices to unblock your path to growth, funding, or exit.

If you're facing a gap between ambition and reality, let’s connect.

Thanks for taking the time to write the playbooks! So much here for operators to put into their toolkits